Overview

In the spring of 2022, Better Health Together commissioned research firms Mathematica and Comagine Health to conduct a landscape analysis of Eastern Washington’s community-based care coordination system. The project’s goal was to identify the current state of care coordination and opportunities to create an improved whole-person model that will better meet the needs of residents and communities. By collecting data via surveys, interviews, focus groups, and publicly available documents, the analysis identified four current themes of care coordination in Eastern Washington and suggested promising approaches to improve whole person care and advance equity throughout the region.

Using this Landscape Analysis and Roadmap as a tool and a guide, Better Health Together will continue to grow and strengthen our efforts to develop a sustainable, collaborative, culturally responsive community-based care coordination system in our region. We invite you to read the report, share it widely with your networks, and use it to inform your care coordination work.

We anticipate that investments in community-based care coordination will be an integral part of the Medicaid Waiver renewal, and we will learn more about what this looks like in 2023.

Themes

There are diverse needs and considerations for providing whole-person care in Eastern Washington, and providers lack sufficient resources to support and facilitate effective care coordination.

The community members and service providers interviewed identified a broad spectrum of needs to consider when providing whole-person care. Participants consistently emphasized the need for mental health supports, a large care coordination gap in the community, as well as assistance with health-related social needs (such as transportation, housing, and financial instability). Respondents also noted dental, spiritual, and emotional needs.

Most survey respondents (85 percent of all types of providers) are screening consumers for health-related social needs, but only 68 percent of social service providers are screening individuals for health care needs (including mental and behavioral health needs), suggesting there is still work to be done to identify and meet each person’s overall needs.

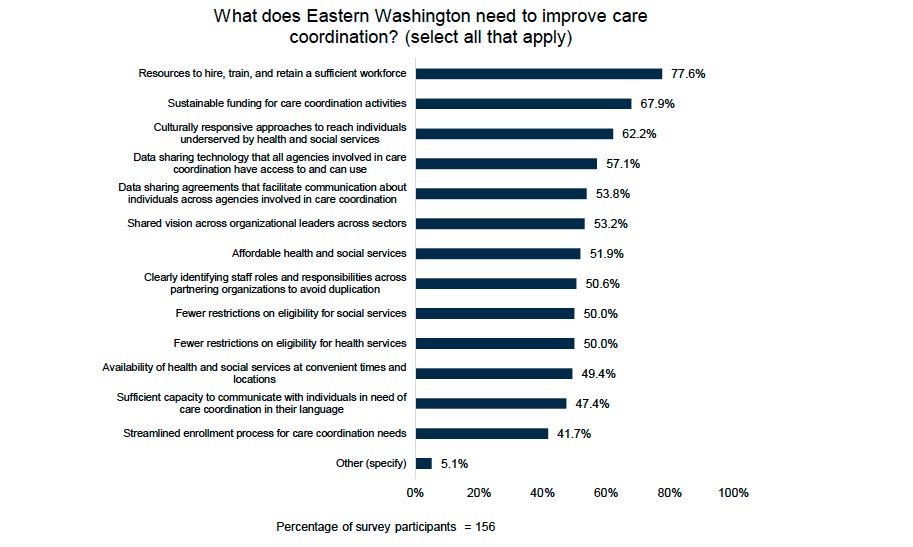

Diverse, population-specific needs. Whole-person care requires recognizing that different populations have different needs. Many interview and focus group participants highlighted the unique needs of particular populations. One participant noted that the definition of care coordination should include cultural relevance to recognize the interconnectedness with communities and how the one-size-fits-all approach doesn’t necessarily meet the needs of everyone. For example, participants identified specific needs of the increasingly aging population, such as safe and supportive long-term housing for people living with dementia. LGBTQIA+ youth may need supports for gender-affirming care and, more generally, feeling safe to openly share and express their true identity when receiving and coordinating care. Residents of rural communities have less access to broadband Internet, which limits their options for accessing virtual services and other online supports. Participants highlighted the importance of language considerations for BIPOC and tribal communities. Similarly, nearly two-thirds (62 percent) of survey respondents recommended using culturally responsive approaches to reach individuals underserved by health and social services.

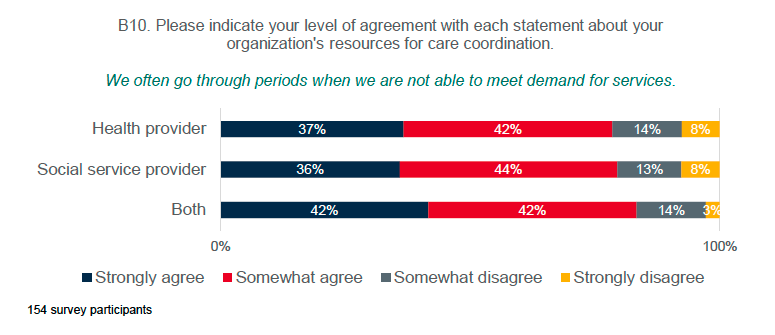

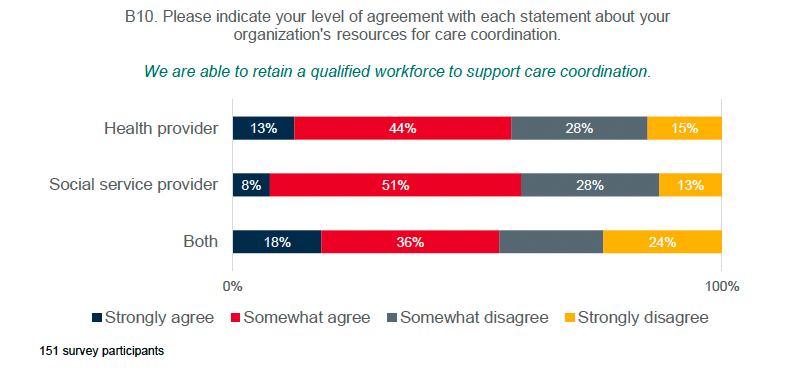

Limited workforce and funding. Organizations in Eastern Washington lack the staff capacity to sustain care coordination activities. Results from the survey highlighted the extent of this challenge. High proportions of respondents agreed that “We often go through periods when we are not able to meet demand for services” (80 percent) and “We often go through periods when we do not have adequate staffing to support care coordination activities” (81 percent). Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) agreed that “We often go through periods when we do not have adequate funding to support care coordination activities.” While over half (57 percent) agreed that “We are able to retain a qualified workforce to support care coordination,” only 13 percent strongly agreed with the statement. When asked how to improve care coordination, the top two needs survey respondents most frequently selected were (1) resources to hire, train, and retain a sufficient workforce (78 percent); and (2) sustainable funding for care coordination activities (68 percent).

Staff with cultural sensitivity and lived experiences. During interviews and focus groups, participants expressed the need to hire staff across all sectors of the care coordination system, including frontline workers, such as community health workers and care coordinators. These workers can help consumers navigate their care. Participants also noted the importance of training providers in cultural competency and addressing stigma and hiring qualified staff with lived experiences to provide care with an empathetic lens. Consumers further supported this perspective and stated that empathy was important to them when seeking care and empowering themselves to self-advocate. Interview and focus groups participants identified solutions to expanding capacity requires investments across the individual, organizational, and systems levels. These include cultural humility training for staff, livable and competitive wages for care coordination staff and reinvestment in community-based ownership, and safe and affordable housing for the broader population.

Organizations are already connected and collaborating but lack the systems, tools, and processes to effectively coordinate care.

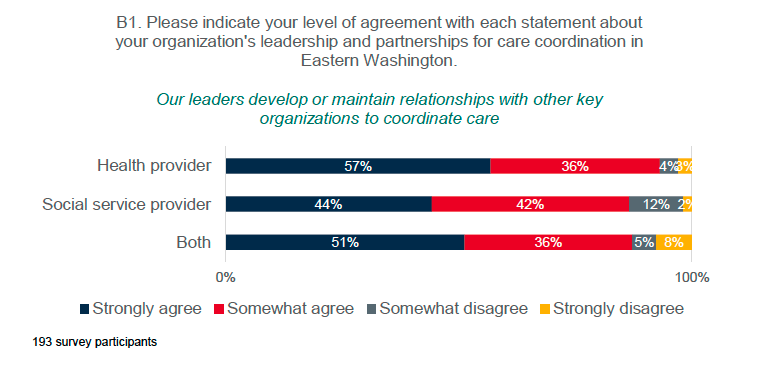

Survey respondents indicated their organizations generally had the right partnerships to support care coordination. Survey respondents had high levels of agreement with statement about leadership being committed to working across organizations to coordinate care for people underserved by health and social services (92 percent) and developing or maintaining relationships with other key organizations to coordinate care (89 percent), though a higher proportion of health providers agreed with these statements than social service providers.

Most also agreed that their organization consistently communicates and coordinates with a range of health and social service providers to deliver whole-person care (84 percent), commits sufficient resources to coordinate care for people underserved by health and social services (83 percent), and has the right partnerships to address whole-person care needs (82 percent).

Most (83 percent) respondents indicated that, when direct service providers do not know where to make a referral, they reach out to a trusted person(s) to determine an appropriate referral, though fewer social service providers agreed with this statement than health providers (78 percent versus 87 percent, respectively).

While three-quarters (76 percent) of providers agreed that providers within their organization use a consistent process to refer individuals to appropriate health care providers, only 54 percent of social service providers agreed with this statement, compared to 85 percent of health providers. Providers working with youth expressed identified a common pain of lack of awareness of resources for youth populations and referrals for youth organizations.

Both survey respondents and interview and focus group participants described barriers that interfere with effective care coordination processes, including the following:

Administrative burdens around completing applications. Interview and focus group participants identified the toll the application processes can place on those seeking care. For example, online applications may be inaccessible and confusing for specific populations, such as elderly clients or those with limited digital literacy. Having to complete multiple applications which ask the same questions may have the effect of repeatedly retraumatizing those who are seeking care. Also, when faced with limited in-service capacity, some providers have instituted approaches to prioritize who receives care—a process that effectively makes consumers compete to demonstrate who is most traumatized.

Delays in receiving services. Administrative hurdles and capacity constraints create delays in providing services to clients. Consumers expressed frustration in the length of time it took to receive resources they applied for, and providers shared those same frustrations over the prolonged delays after referrals were made. Both described waiting lists that were almost three months long. To address the administrative burdens of care coordination, participants suggested streamlining the referral and application process. For example, one participant advocated for creating a phone system where a community member can call and be transferred to a service directly. A consumer suggested a community-based doctor model, where medical teams go directly to a consumer’s home to perform regular check-ins and preventative care.

Inequitable eligibility criteria. Interview and focus participants also expressed frustrations in payments available for services. Providers mentioned the limitations of Medicaid, where the provision of certain services, such as transportation, are not available for reimbursement despite transportation being a high need for the communities, and certain providers turning down Medicaid because they are unable to match the fees that private insurance companies are able to pay.

The bi-directional information sharing foundational to coordinating care doesn’t occur consistently, due in part to limits in technology and infrastructure constraints.

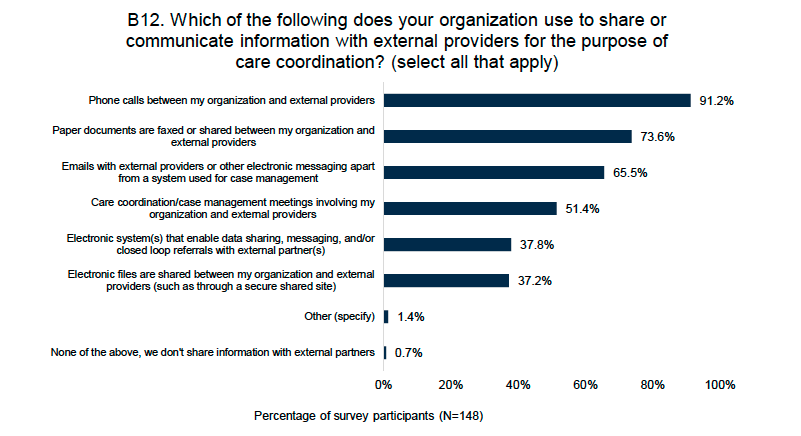

Service providers and care coordinators in Eastern Washington are using many communication channels to coordinate care. Nearly all (91 percent) of survey respondents use phone calls to share or communicate information with external providers, almost three-quarters (74 percent) share paper documents, and two-thirds (66 percent) use email or electronic messages outside of a case management system.

-

Social service providers are much more likely to use email than health providers (77 percent versus 65 percent), and they are less likely to use paper documents (44 percent versus 87 percent) and phone calls (85 percent versus 93 percent).

-

Most survey respondents reported phone calls (71 percent of those who use them) and emails (66 percent of those who use them) enable them to coordinate care most effectively, though social service providers preferred emails while health providers preferred phone calls.

-

Among those who use them, some of the less frequently used communication methods were also rated as effective for coordinating care, including electronic systems that enable data sharing, messaging, and/or closed loop referrals (79 percent of those who use them) and care coordination and case management meetings (71 percent of those who use them).

Survey respondents did not perceive current information sharing systems and processes as sufficient for care coordination. Fewer than half (43 percent) agreed that direct service providers receive feedback about resolution or required next steps for addressing the individual’s needs after making a referral. Shared referral platforms and community information exchanges can enable secure information sharing about clients’ needs across sectors and, in some cases, bidirectional communication to close the referral loop; yet, fewer than half of respondents felt that they have sufficient technology system(s) direct service providers to deliver whole-person (13 percent strongly agreed and 35 percent somewhat agreed). Only 32 percent of respondents reported their organizations used an electronic system that enables data sharing, messaging, and/or closed loop referrals, but 79 percent of those who do use such systems felt it was the most effective coordination method.

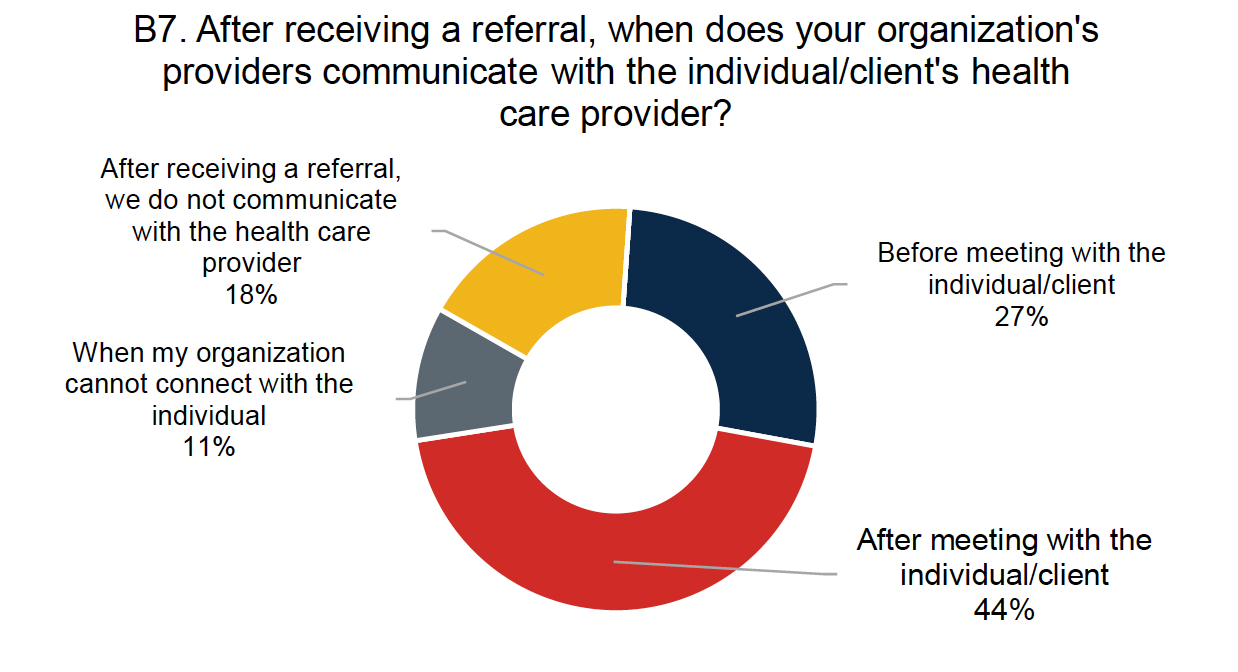

Inconsistent referral oversight. When referrals to external organizations do happen, there are few processes for follow-up to ensure that client needs are met. Social service providers also commonly reported receiving referrals from health providers, including mental or behavioral health providers (79 percent). However, communication between health and social service providers about these referrals was less common. Fewer than half (44 percent) of social service providers reported communicating with the individual’s health care provider after meeting with the client, and an additional 27 percent communicated before the social service provider met with the individual. Providers overall noted that they are often required to look across multiple data systems to connect with various organizations for a status update on one referral.

Interview and focus group participants identified the expanding role of technology in care coordination and how it can either improve or limit the ability for communities to receive care. For some providers, regularly convening virtually, created opportunities for collaboration across sectors to identify gaps in services. However, the growing use of online communication tools revealed an apparent divide between rural and urban care delivery services. While community service providers in urban settings were more able to transition using online platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic, rural service providers struggled to provide coordinate care virtually. For organizations serving rural and tribal communities, broadband limitations prevented providers from accessing online training, telehealth services, and other services requiring online applications. In addition, many residents had no experience with using online services or were not trained on how to navigate and utilize these tools effectively.

Several providers discussed the need to improve broadband access and make online services more available, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic moved many services online. For example, one organization used creative solutions during the COVID-19 pandemic, such as partnering with local libraries to provide telehealth kits with laptops to clients in a rural region; the clients could participate in their telehealth visits from their parked cars within the library’s Wi-Fi reach.

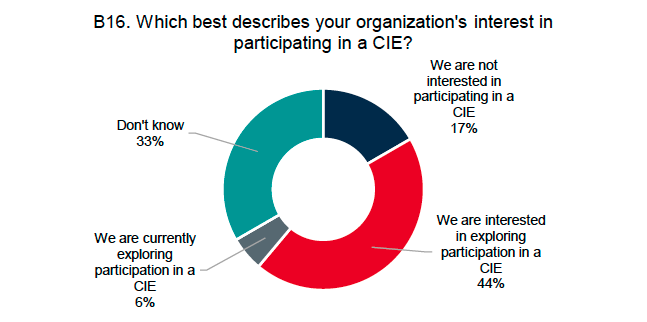

Community information exchanges. Despite the growing importance of community information exchanges (CIEs), respondents across the sample were not aware or did not use a CIE. Over half of survey respondents (52 percent) did not know whether their organization participates in a CIE. Of those who were able to answer the question (79 respondents), only 29 percent reported that they do participate in a CIE. Among those whose organizations do not currently participate in a CIE, half are exploring or interested in exploring participation in the future; an additional one-third were unsure (Exhibit 5).

Interview and focus group participants thought a CIE could be effective in closing knowledge and communication gaps in referral processes, but others were concerned about the lack of a consistent platform for tracking referrals. Organizations were also worried that privacy issues would create access issues, such as firewalls, and that existing data- sharing policies would make it hard to share certain consumer information.

While hiring staff with cultural sensitivity and lived experience was identified as a solution to capacity constraints for care coordination, interview and focus groups participants also emphasized the how—that is, how relationships and empowering the consumer are at the core for providing care. Consumers often expressed frustration in the lack of personalized care and the trauma they experienced from engaging in current health care systems. These include doctors not treating patients with care, lacking interpersonal skills, being discriminatory towards disproportionately impacted groups (such as the LGBTQIA+ community), and treating patients through a deficit-based lens. Youth participants expressed frustrations about often being dismissed and not taken seriously when seeking care. Providers expressed dissatisfaction from operating in silos, lack of awareness of the community resources, and limited training in understanding community needs.

Interview and focus group participants offered suggestions for how relationships could improve in the future. These relationships include those between providers and those between providers and consumers. Both processes would require providers and consumers across social services and health care to engage in self-reflection to address their own stigma and biases.

Other approaches identified include making care coordination more accessible, personalized, and legible. Examples include listening, educating, and advising the consumer using trauma-informed language, as well as community outreach and home visits to meet the consumer where they live in a comfortable environment that is free from judgement.

Report

Above: Scrolling image gallery with responses to select survey questions. Click the Appendices button above to view the full survey and all responses.

Roadmap

Fostering and supporting sustainable, whole-person care coordination in Eastern Washington will require action at individual, organizational, and system levels. See the image below for examples of potential solutions that emerged from our landscape analysis. Selecting, designing, and implementing any policies, practices, or changes should be tailored to—and done in partnership with—the communities for which they are intended. Taking context into account to ensure that the intervention is meaningful, relevant, culturally responsive, and trauma informed will benefit impacted communities and has the potential to improve community health.

What’s Next?

What’s Next?

For providers of care coordination service

-

Use the report to inform improvements to care coordination processes and systems.

-

Use findings in grant applications and to generate financial support for care coordination efforts.

For Better Health Together:

-

Share the report widely with partners and community members.

-

Continue to develop and resource the BHT-based Care Connect System, which provides digital navigation, Covid response, and other care coordination services via a hub-and-spoke model. Community health workers based at organizations that address health-related social needs provide services to community members across Eastern Washington.

-

Support behavioral health workforce development via Behavioral Health Forum initiatives. Read more about the Forum at this link.

-

Work collaboratively to identify and address access and equity issues by supporting community-led initiatives (like rural school-based health projects and county collaboratives) and funding opportunities (like the Community Linkages RFP and the Community Resilience Fund RFP).

-

Connect with and learn about other efforts to improve care coordination across the state. For example: Healthier Here’s work in King County (click here to see an executive summary of their community-based care coordination landscape analysis).

-

Advocate for community-based care coordination policies and practices that elevate community voice and a build a representative, community-based workforce.